|

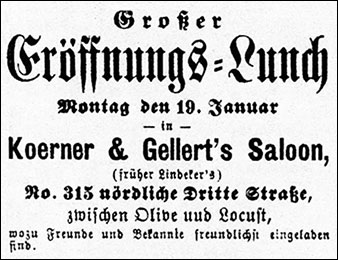

Koerner's The Koerner brothers were born in Germany. Charles was born in 1844, Otto in 1851, Ernst in 1853 and Albert in 1859. All four immigrated to the United States and settled in St. Louis. Charles Theodore Koerner immigrated from Germany in 1866 with his wife and their seven children. They settled in St. Louis after living for two years in Baltimore. By 1870, Charles Koerner was working as a waiter, and then a bartender, at St. Louis House, and in 1873, as a bartender at August Dorguth's saloon. In 1874, he partnered with Ernst Gellert in a saloon at 315 North 3rd Street. The two opened a second saloon at 610 North 3rd in 1875, and by 1876, Gellert had withdrawn from the partnership.

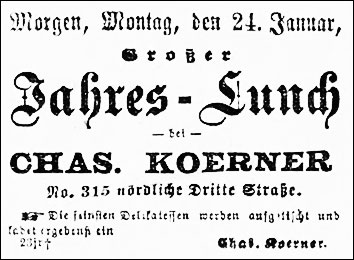

In addition to alcohol, Koerner offered German

fare for lunch, which he advertised in the German language newspapers.

Ernst F. Koerner came to St. Louis from Germany in 1870. He worked as a bartender at his brother Charles' 315 North 3rd Street saloon from 1875 to 1878, living upstairs. By 1880, he was running the saloon at 610 North 3rd. Albert Ernst Koerner arrived in St. Louis in 1875. He worked as a waiter at Tony Faust's restaurant in 1878. In 1880, he lived with his brother Charles on Lafayette Avenue ― the same year the two brothers established Koerner's Garden.

Koerner's Garden was located at the corner of

Second Carondelet (South 18th Street) and Lafayette. It was one of

the most popular entertainment venues of the time, with the first

open-air concerts and the first open-air theater in St. Louis. After

fourteen years, in 1894 Koerner's Garden was moved to the corner of

Kings Highway and Arsenal.

In November of 1882, Albert Koerner married Anna Lederer in South Bend, Indiana. Upon returning to St. Louis, they took up residence at 1627 Carroll and began having children. Albert J. was born in 1883, Arthur E. in 1885 and Victor H. in 1904. The latter was named for the composer Victor Herbert, who had "delighted in Koerner's food and delighted him with music in return." Charles and Albert Koerner opened a saloon together just north of Koerner's Garden. It was commonly referred to as the Koerner's Garden saloon. On Sunday, July 29, 1883, a law went into effect banning the Sunday sale of alcohol in St. Louis. Charles Koerner was an outspoken critic, as reported in the July 29, 1883 edition of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

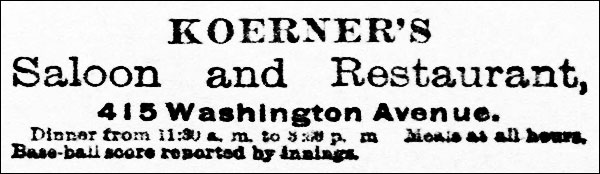

In 1885, Albert Koerner relinquished his

involvement in Koerner's Garden and its associated saloon to his

brother Charles, and opened a new saloon and restaurant at 415

Washington Avenue with his brother Ernst. Ernst Koerner

died of a liver abscess later that year at the age of 31. He left

his interest in the 415 Washington establishment to Albert. From

that point forward, possibly to honor his deceased brother, Albert

Ernst Koerner began calling himself "Ernst Albert Koerner,"

or more commonly, "E. A. Koerner."

A brief review of Koerner's new restaurant appeared in the September 10. 1886 edition of The Jewish Free Press.

On October 23, 1887, a fire broke out in the building occupied by the Woolman-Todd Boot and Shoe Company at 413 Washington, which threatened to destroy the entire block of buildings between Fourth & Broadway and Washington & Christy. The three-story building at 415 Washington, occupied on the first floor by Koerner's Saloon and Restaurant, proved a total loss. * * * * *

The Merchants'

Restaurant was established at 616 Washington Avenue in the early

1880s. In 1888, E. A. Koerner took over management of the

restaurant, later branding it as The Merchants' Restaurant and

Oyster House. Otto Frederick Koerner, the fourth Koerner brother, immigrated from Germany to St. Louis in 1890 with his wife and their four children. He worked for his brothers for a number of years; he was manager of The Merchants' Restaurant by 1897. In August of 1899, The Merchants’ Catering Company was formed. E. A. Koerner was president and Otto Koerner was vice president.

The new company

closed the 616 Washington location and opened a new restaurant at

408 Washington in a space which had housed the Grand Cafe. They

called it The Merchants' Catering Company Restaurant and Oyster

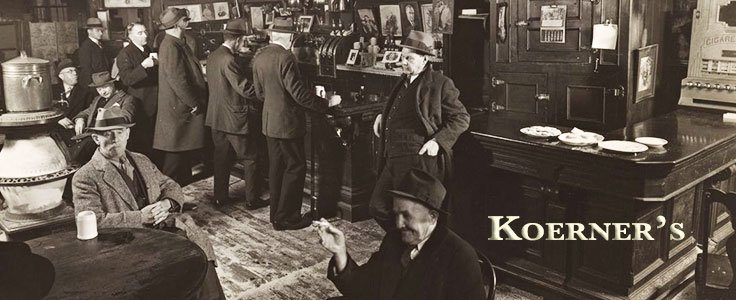

House, but it came to be known as simply Koerner's. With the move to the 408 Washington space, the prosperity which had come to the Koerner establishments flourished. In its prime it was considered one of St. Louis’ best and had a nation-wide reputation as a place for good things to eat. Over the entrance, patrons were lured by the sign, "Your Father Used to Eat Here." The cool, dimly lighted dining room, which housed the long bar, combined the aspects of a public house and a clubroom. Businessmen gathered in congenial groups about round tables and dallied over well filled dishes. It was a popular meeting place for merchants, travelers, stockmen from the East Side, politicians and race-horse followers. Downstairs was the men's eating room; upstairs was the family restaurant. Orderliness ranked with cleanliness as an unwritten motto. Koerner's was no place for barroom brawls as in corner saloons, where whisky held way. The dining room was presided over by E. A. Koerner, known to all of his patrons as "Papa." His lifelike portrait graced the rear wall, beneath an American flag.

Koerner, who for many

years weighed 350 pounds, was himself a lover of good food.

Prodigious feasts were served at a big round table reserved in the

restaurant for "Papa" Koerner and his friends. There he was king at

his own banquet board. Koerner’s was not an eat-and-run place, where a sandwich and a bottle might be ordered for a hasty meal. Men ate long and leisurely in those days. Koerner’s savory dishes were known far beyond the confines of St. Louis. Koerner once said that 30 per cent of his patronage was local and the remainder was made up of visitors who had heard about him and his cuisine.

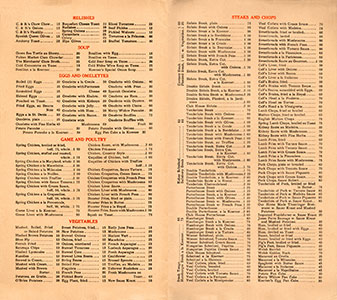

Koerner's offered high

quality German fare, including wiener schnitzel, potato pancakes and

kartoffel salad. In the days before prohibition, an equally alluring

list of drinkables was provided for guests, but beer, in true German

fashion, was the prime favorite. It was Koerner's boast that he had

been the first to bring certain brands of Rhine wine, beer and

cheese to St. Louis. While many restaurant owners of the day ran into trouble with the authorities for offering contraband game on their menus, Koerner was involved in only one such episode, detailed in the November 12, 1909 edition of the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.

Even the advent of the automobile, which resulted in the establishment of dozens of eating places in rural areas, had no effect on the prosperity of Koerner’s business; his dining rooms remained crowded. Koerner's downfall was prohibition. His business fell off more than fifty per cent with the advent of the Volstead Act, which prohibited the sale of alcohol. Beginning in early 1920, Koerner was arrested four times by federal officers and once by the city police for violating prohibitory laws. He paid $2000 in fines into the federal treasury and $100 into the city's purse. In March of 1921, Koerner was sentenced to six months in jail and fined $1000 for selling liquor to a prohibition agent. His attorneys appealed, presenting a physician's certificate showing that Koerner was in a precarious state of health, with "diabetes, dropsy and heart disease." A court appointed physician agreed, declaring it would be "inhuman" to commit Koerner to jail. In early 1923, federal judges decided to drop the mandate directing Koerner to serve his sentence. E. A. Koerner retired from the restaurant business following his brush with incarceration. After spending time in a sanitarium in St. Waukesha, Wisconsin, he regained his health.

Ernest Albert Koerner died on October 15, 1926 at the age of 66. * * * * * After he retired, E. A. Koerner's three sons took over The Merchants’ Catering Company, with Arthur Koerner serving as manager. Like his father, Arthur was repeatedly fined for violating the prohibition law. "They were picking on our place," he once said. The government was suing to padlock the restaurant, when the Koerner brothers decided to close it for good, “beating the government to it." The "Your Father Used to Eat Here" sign over the entrance was taken down and Koerner's closed quietly on June 26, 1924. * * * * * The Koerner's building at 408 Washington Avenue was razed not long after the restaurant closed. A "modern" three-story structure, with the same address, was completed early in 1925. The new building lasted just over 40 years; it was razed in 1966. Its final tenant was Jack Carl's 2˘ Plain.

Copyright © 2023

LostTables.com |

.