|

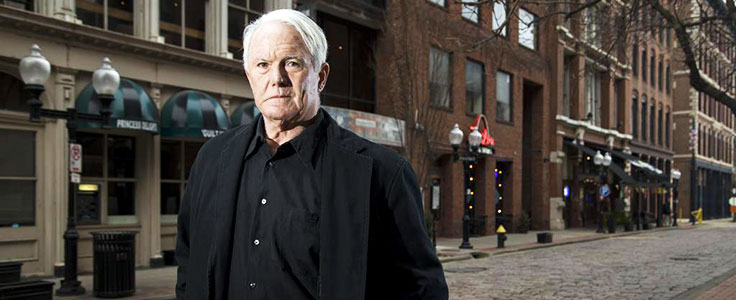

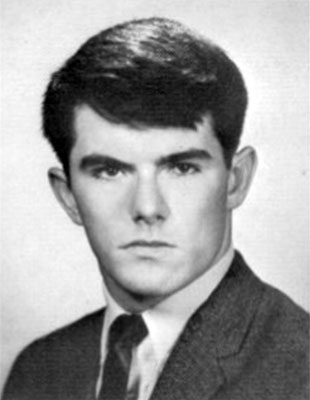

John Clark John David Clark Jr. was born at St. Mary's Hospital in Evanston, Illinois on September 6, 1949. He lived with his parents and siblings in the northern Chicago suburbs of Des Plains, and then Mount Prospect, until he was ten-years-old, when his father's job as a textile salesman took the family to St. Louis. They settled in a large house in Spanish Lake, on the bluffs of the Missouri River. Clark attended St. Louis University High School, graduating in 1967. He then entered Parks College in Cahokia, thinking he would be an aircraft maintenance engineer, although his earliest ambition was to be a policeman.

The first Vietnam War draft lottery was held on December 1, 1969. Clark's birth date was drawn sixth.

A friend convinced Clark to enlist in the National Guard. Clark told the enlistment officer he wanted to go into law enforcement, so they made him an MP. Discharged after a six month stint, he returned to college, transferring from Parks College to St. Louis University. Still aspiring to be a policeman, Clark took sociology courses in SLU's School of Commerce and Finance.

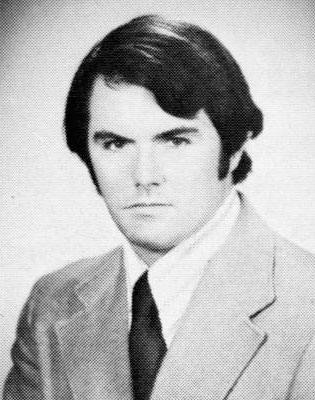

Clark graduated from St. Louis University in

1972 with a bachelor's degree in business.

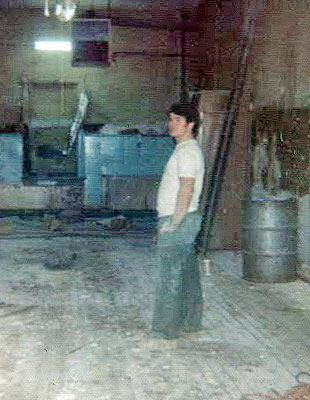

Usselman's Market had been a St. Louis institution at the northwest corner of Spring and Laclede since 1920. The market was a popular spot for Cardinals and Browns baseball players and managers who leased apartments in the area or stayed at the Coronado Hotel. Usselman's closed in 1969. The two-story building was acquired by John A. Joyce, a lawyer and alderman, as a fee for legal work. It was not a prime real estate holding. The downstairs was vacant; the upstairs was uninhabitable, the walls crumbling. In his final semester at Saint Louis University, John Clark walked by the boarded-up old grocery store and decided it would be a good place to open a bar.

Clark acquired a three-year lease on the first-floor space. He started with $7000, with $5000 borrowed from his father. After four months of sanding down old plank flooring, knocking off plaster to bare a brick wall, putting in plumbing, rough-wood paneling and a bar, and building an inventory, he had about $20 left in his checking account.

Clark called his new venture Fridays, so named

by his girlfriend and based on the campus adage, TGIF ― Thank God

It's Friday. Fridays

debuted in late February of 1972.

Furnished with 15 tables to seat 60, Fridays served a campus crowd of 300 opening night.

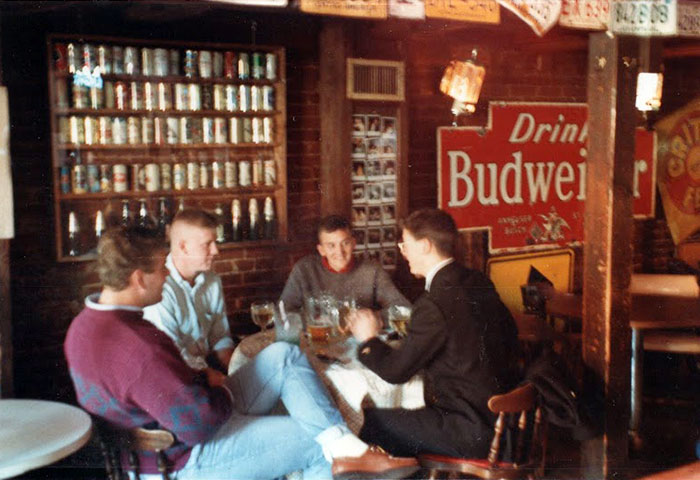

Fridays' decor was described as rustic, with a fine old oak door and cafe curtains made from burlap bags. An American flag, about 4 feet by 7 feet, was tacked up on the paneled wall.

Clark's mother, his sister and a family friend helped behind the bar serving the lunch menu, which included roast beef and ham and cheese sandwiches for 75 cents, and cackle berries (hard boiled eggs) for 15 cents. Inside of a year, Fridays had broken records for selling beer. Pinball had become a craze again and Foosball arrived and Fridays became one of the hottest college hangouts in town.

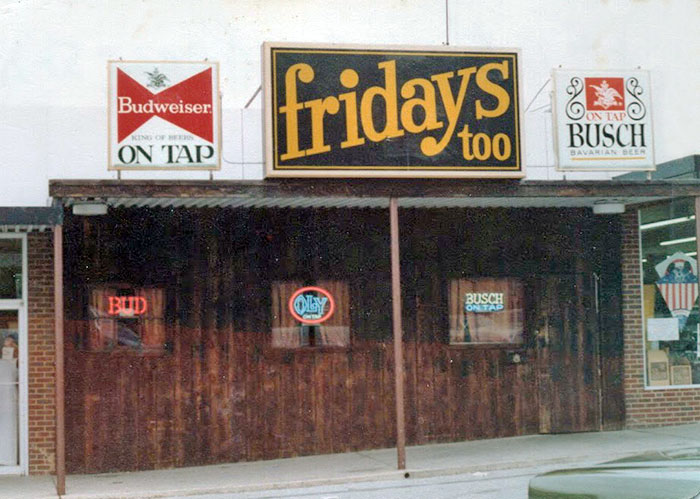

Clark noticed that a lot of the college crowd

frequenting his bar had ID's from the University of Missouri-St.

Louis. So in early 1973, he opened a second Fridays at 8911 Natural

Bridge, near the UMSL campus. Fridays Too, as it was called, caught

on too.

In 1974, Clark opened a third Fridays in Illinois.

In 1973, the national TGI Fridays chain sued

Clark, claiming ownership of the "Fridays" name. After five years in

federal court, the case was settled, with the Dallas based company

buying the name from Clark for $10,000. In 1978, Clark renamed his

St. Louis taverns Clark's and Clark's Too. Clark's at Spring and

Laclede would continue to serve SLU students until 1992.

John Joyce, who owned the building at Spring and Laclede which housed John Clark's first floor bar, died in August of 1972.

Clark opened Pie In The Sky Pizza at 3 North Spring, with a walkup entrance just north of his tavern.

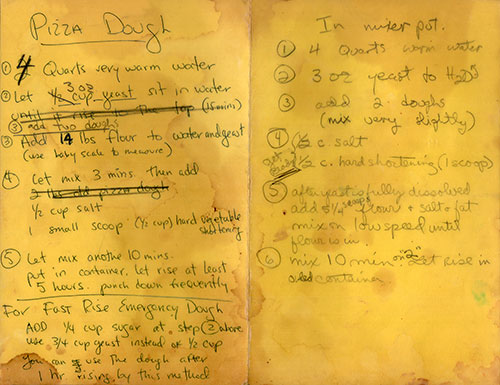

Clark "borrowed" the recipe for his pizza dough from Shakespeare's Pizza in Columbia.

In 1975, the city of St. Louis approved a development plan for Laclede's Landing, the nine-square-block area sloping from Third Street to the levee, between the Eads and Dr. Martin Luther King bridges. By 1978, Muddy Waters, Mississippi Nights, Kennedy's, First Street Alley and the Old Spaghetti Factory were booming along the Landing's narrow cobblestone streets. The Old Judge Coffee Building at 708-710 North Second Street was originally built in 1883 for the offices of Scharff & Bernheimer, one of the largest Mississippi River shipping firms of the era. The five-story building was purchased by Old Judge Coffee in 1918 and converted into a factory and spice warehouse. In 1977, the Old Judge Coffee Building was purchased by Hoffmann Partnership, an architectural firm in Clayton. After more than $1 million dollars in renovation work, Hoffmann moved their headquarters into the building and was seeking other tenants. They approached John Clark about the basement space on Clamorgan Alley, in the rear of the building.

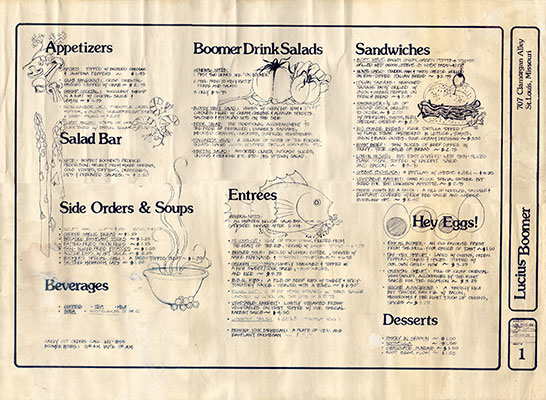

In November of 1978, Clark became a

restaurant owner on the Landing. He sold his Belleville bar, and

with $250,000 in loans, he opened Lucius Boomer at 707 Clamorgan Alley, in the basement of the Old

Judge Coffee Building.

Lucius Boomer took

its name from a nineteenth century bridge builder who was one of

James Eads' principal competitors. The basement space was a long,

narrow room with stone walls displaying historical drawings. The

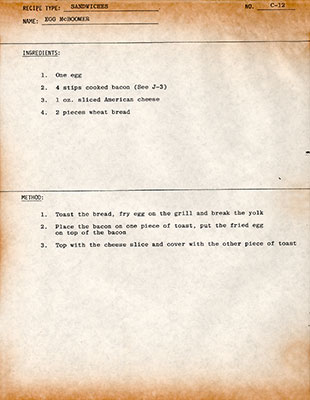

restaurant's menu resembled a large blueprint with engineer print. The range of food touched on Mexican, Italian, Chinese and European. The original menu featured an egg dish which Clark called Egg McBoomer.

Lucius Boomer was known for its Crab Rangoon appetizer.

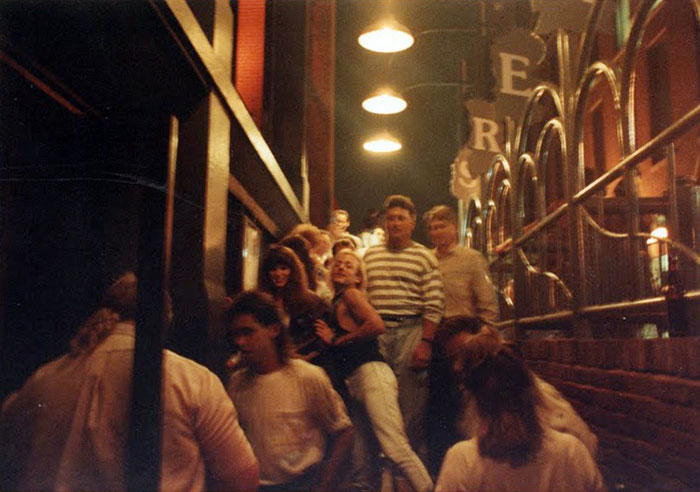

Boomers, as it came to be called, had live entertainment seven nights a week, featuring a Top 40/dance/classic rock formula. There was no cover charge. Clark proudly advertised, "always a party, never a cover."

Lucius Boomer received citations, awards,

articles and mentions from both local and national newspapers and

magazines. They were a regular entry in Restaurant Hospitality's

top 500 restaurants in the United States. In 1984 and 1985 Boomers

was listed in Playboy Magazine's "Best and Hottest" club

survey for the single-minded. In February of 1991, Traveler

Magazine called Lucius Boomer "the place to dance in St. Louis."

In addition, the restaurant routinely won year-end awards from the

Riverfront Times for best bartenders, waitresses, atmosphere,

drinks and food.

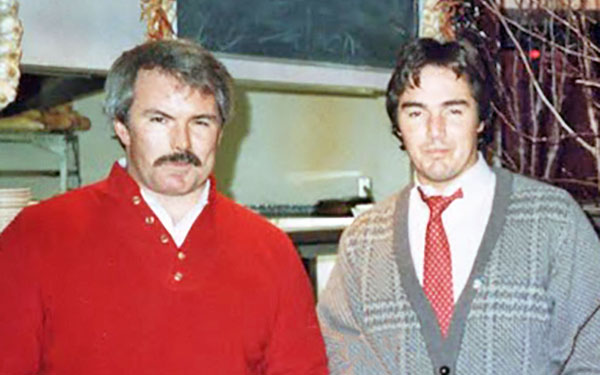

Clark hired Tim Mallett as manager at Boomers, and Mallett soon became a close associate and Clark's general manager. In January of 1980, Clark began thinking expansion again.

The large, one-story building at 8215 Clayton Road, across from Westroads Shopping Center, had been The Cupboard restaurant before it was Abernathy's.

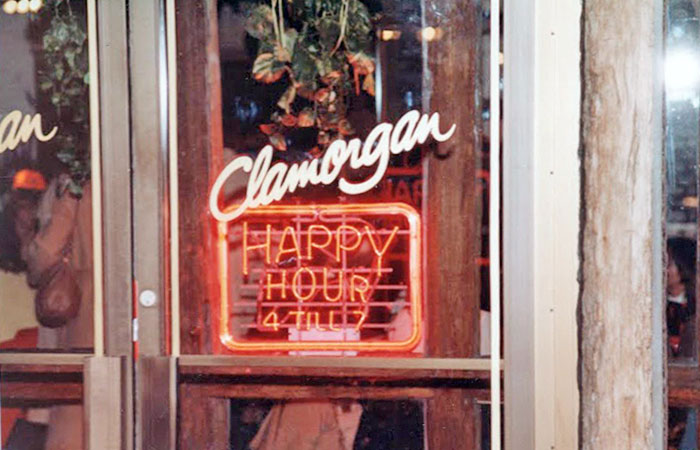

Clark leased the space and opened Clamorgan on

June 18, 1980, the name derived from Clamorgan Alley, the address of

his restaurant on the Landing.

Clamorgan was an instant success. Clark rearranged the

space, removing

many of the antiques and artifacts of the previous decor. There was a bar

featuring live entertainment to the right,

and a dining room to the left, off the main entrance. There were other

dining rooms farther to the rear and a second bar. Servers wore

preppy uniforms of khakis, alligator-emblazoned golf shirts and

loafers.

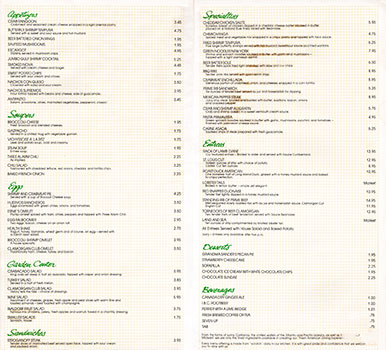

Clark's menu, which he used for both lunch and dinner, had a Mexican flavor, with nachos, gazpacho, huevos rancheros, chimichangas, enchiladas and a Mexican pepper steak.

After five years in business, Clamorgan boarded its doors on August 31, 1984. Clark cited unsuccessful lease negotiations as the reason for deserting the site.

Clark opened his downtown restaurant the following year. He debuted John Clark's Olive Street Bistro on October 3, 1985 in the St. Louis Place Building at 420 Olive Street.

The bistro's main level contained the bar with a stand-up area and lounge, with dining areas on the upper and lower levels. The decor contained shades of deep reds and blacks, with teal green and wood accents.

Photographs of buildings once housed on the

site of the bistro hung on the walls, along with plaster casts of

terra cotta work and the lion's heads from the old Commerce Bank

building.

Clark's menu, which was the same for both lunch and dinner, was eclectic, combining Cajun/Creole and Italian cuisine with the all-American favorite, the hamburger, plus steaks, seafood and salads.

While John Clark's Olive Street Bistro got good reviews, the restaurant struggled.

As of August 31, 1987, the space had been converted into a mini-version of the successful chain of Caleco's restaurants. About the time Clark closed his bistro, he also parted ways with his general manager, Tim Mallett.

In November of 1988, Tim Mallett opened Blue

Water Grill at 2607 Hampton.

Lucius Boomer continued to boom. In the summer of 1988, Clark expanded his restaurant, adding a second dining room and bar, and a private party room. He had enlisted the Pasta House's Kim Tucci to go with him to Jefferson City to lobby the legislature to extend his closing time from 1:00 am to 3:00 am.

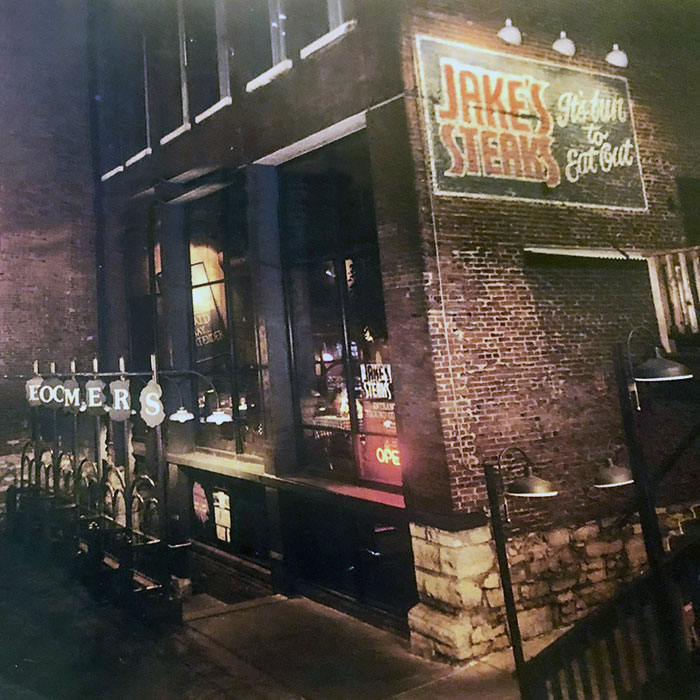

The space above Clark's basement spot in the Old Judge Coffee Building had originally been occupied by Chapin's, a restaurant and bar. In 1981, Roma's in the Landing, a rib joint, opened in the space, and in 1982, Roma's was reopened as Uncle Sam's Plankhouse. Uncle Sam's closed early in 1990. Someone gave Clark's name to the bank, thinking he would be interested in the space. He wasn't initially, but the bank made him an offer he couldn't refuse. He leased the space for a new restaurant, which he called Jake's Steaks.

The restaurants which had occupied the space above Boomers had their entrance on North Second Street. Clark confined his new restaurant to the lower level of the space, and changed the entrance to Clamorgan Alley, a portal which had worked well for Boomers.

By August of 1994, business at Jake's had

increased beyond the capacity of Clark's condensed space. He

expanded into the upper level and flip flopped the entrance back to

North Second Street. And by the beginning of 1999, Clark had

completed a 1,200-square-foot addition, with a new private dining

and party area, which seated 70, raising Jake's capacity to 250.

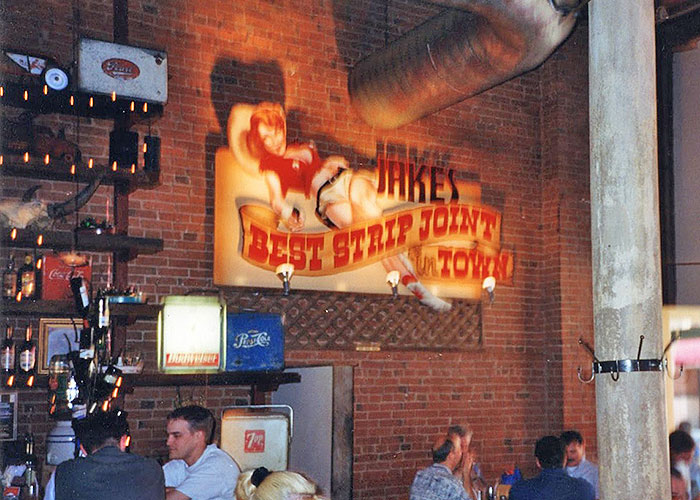

Clark dubbed Jake's the "Best Strip Joint in

Town." The decor included exposed brick walls, open-beam ceilings,

vintage pinball machines and old advertising signs.

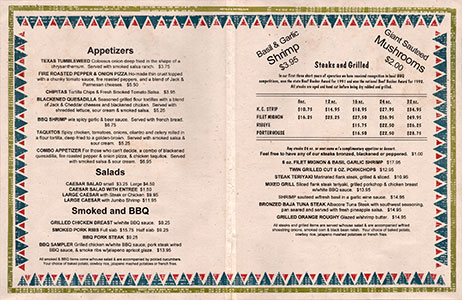

Jake's Steaks was a

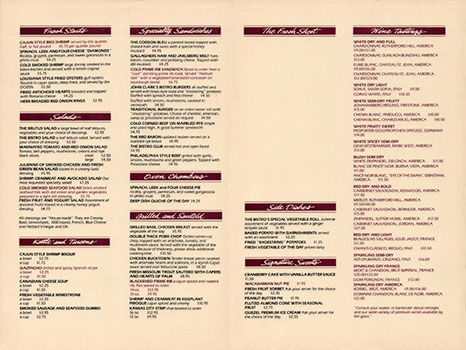

classic steakhouse with a southwestern flair. Diners chose from four

cuts of steak, then chose a size from 8 to 32 ounces. House-made

rubs and sauces went a step further to customize each order. Pork

chops, chicken, seafood and salads shared the menu.

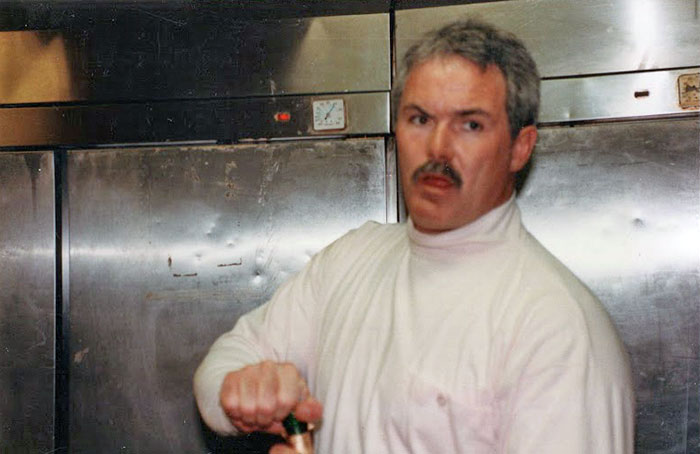

Blackened chicken linguini was the big seller at lunch. When Tim Mallett left Clark to go out on his own, John Wilson took over as Clark's general manager. Wilson had gone to Forest Park Community College for culinary arts and then joined the navy and cooked for 4 years on a carrier and destroyer. Although he was not a formally trained chef, he said, "I managed restaurants all my life and when the cook doesn’t show, you had better know what to do." Wilson started with Clark in 1985 and stayed with him until 2008.

In early 1997, Clark purchased the Old Judge Coffee Building for $1.1 million. To fill a vacant space on the ground floor, he decided to open another restaurant. Clark debuted the Diablo Cafe at 710 North Second, adjacent to Jake's Steaks, in August of 2001. The warm decor featured midnight blue, brick red and tan walls, along with mosaics and punched tin sconces. A mix of tables, booths and banquettes accommodated 62 in the dining room. A small bar completed the space. Diablo's cuisine featured an eclectic mix of Mexican, Southwestern and Cajun influences, with touches of Mediterranean and Asian. Their slogan was, "We flavor our spices with food."

The menu was developed

by Clark and Wilson, with consulting

assistance from Greg Perez, who had excelled at Tim Mallett's Blue

Water Grill and his own Painted Plates. House specialties included a

pan-seared crab cake appetizer, with stripings of jalapeno mustard

and roasted red pepper creams, and the Terror of Diablo dessert,

featuring espresso chocolate moose, layered with cinnamon espresso

soaked devils food cake and topped with chocolate glaze. Despite good reviews, Clark's new restaurant closed by August of 2002, a year after it opened.

Not only did Clark sell Gianino the Diablo Cafe, he also sold him Lucius Boomer.

While Boomers was dependent on music for its

success, Jake's Steaks was not. Clark's steakhouse continued to

thrive until he closed it in 2014.

Eventually, the parties ended on Laclede's Landing. The recession, the renovation of the Arch grounds that cut off access to the area, and the end of Rams football at the nearby Dome at America's Center contributed to the decline of the cobblestone-studded historic neighborhood. John Clark sold the Old Judge Coffee Building and retired from the restaurant business. He lives comfortably with his partner of forty years, Mary Louise Helbig, in their home on the Mississippi River in Golden Eagle, Illinois.

And if he had it to do all over again . . .

Clark would do things pretty much the same.

Copyright © 2022 LostTables.com |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||